#UCSciCommSeries Presents: Teresa Ortner

Quick Summary

- Dr. Teresa Ortner, Senior Editor at Communications Chemistry, provided tips and tricks for publishing in nature portfolio journals and other scientific journals. Dr. Ortner also talked to us about what it takes to be a journal editor.

Dr. Teresa Ortner, Senior Editor at Communications Chemistry, spoke to us about writing and publishing in scientific journals with a focus on Nature portfolio journals.

Dr. Ortner completed her doctorate in Chemistry at the University of Innsbruck, Austria before she conducted research as a Postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Riverside. After her postdoc research, she moved to Germany where she worked as an Associate Editor and Freelance Editor for Nature and Nature Communications . Currently, she is a Senior Editor atCommunications Chemistry where she spends her days curating paper submissions. In this role, she is able to remain up-to-date with research and current advances in the field without having to be at the bench.

Communications Chemistry (@CommsChem) is a relatively new, fully online, and open access journal that publishes new insights into all aspects of chemistry research. One exciting aspect of this journal is its shared editorial model with full-time in-house editors complemented by an editorial board that serves as full external editors. Unlike many other journals, the editorial board for Comms Chem is active in research and can offer unique insights into their respective expertise.

Open Access Publishing

Dr. Ortner discussed the benefits of publishing in open access journals, including making scientific knowledge accessible for everyone which improves public understanding of scientific research and increased downloads and citations for open access articles.

While we may think of open access as “free to read” articles after publication, there are actually different “flavors” of open access journals. Dr. Ortner described two flavors:

- The gold route in which the journal provides immediate access to the published paper, allows re-use of the content under CC-BY license, and permits immediate deposit into an Open Access repository.

- The green route permits access to the paper after an embargo period and allows re-use of the content for non-commercial purposes.

Because the publishing costs of open access publishing are charged directly to the scientists, waivers may be available to assist with fees. For nature portfolio publications, a helpdesk is available to help secure funding by emailing openaccess (at) nature.com. You can also find open access funding sources and links to funder and institutional policies here.

Selecting a journal

When selecting the best journal for your paper, Dr. Ortner suggests the AUSTRIA model:

- Advance: Does your work build on recent advances in your field?

- Urgency: How fast do you want your work to be out?

- Scope: Does your work fit within the scope of the journal?

- Target Audience: Who do you want to read about your work?

- Relation/Context: How does your work fit into the field?

- Impact: How significant are your findings?

- Accessibility: Is open access important to you?

With this in mind, what makes a Nature paper?

In general, Nature publishes the most significant advances with the widest implications to any field. For more discipline-specific findings, Nature research journals (e.g. Nature Cell Biology, Nature Materials, etc.) may be more relevant as these journals focus on significant findings that impact a particular discipline. Nature Communications publishes both full-length articles and short communications on new ideas, insights, and technologies.

How to WOW your readers

The most important rule is to think of your reader. Who is going to read your paper? Most likely, scientists, reviewers, and editors. To write for these audiences, some general advice for writing that Dr. Ortner offered was:

- To demonstrate why your work is important rather than just stating what you have done. The reader should not walk away thinking “so what?”

- Read papers you like and find accessible

- Avoid descriptive or chronological writing style

- Guide the reader through the story with a clear structure and logical flow

- Make sure the significance is clear

Additionally, Dr. Ortner emphasized “explain, don’t hype.” Allow your work to speak for itself instead of overselling your research with exaggerations, over generalizations, and hyperbole. Lastly, avoid claims of novelty – as Dr. Ortner explained, “if your research is not new, you would not be publishing about it.”

Breaking down the parts of a paper

Title

Your title should draw the reader in and make the main message of the work clear. It should also be descriptive, but not too detailed or include too many adjectives, jargon, and acronyms.

Abstract

For your abstract, the question you are addressing should be clear and your most important findings should be summarized. Mention critical methodology and notable implications of your work. Avoid including detailed methods, uncommon abbreviations and unnecessary acronyms, and referencing specific figures in the paper.

Introduction

This is where you set the stage. Introduce your question and background of your work. Be smart when selecting your citations and summarize your findings briefly as a lead into your results. While many scientists find this section unnecessary, it is extremely important for early career researchers or other scientists who may be new to the field or topic.

Results

The results are the heart of your paper. Dr. Ortner recommends ordering experiments logically, not chronologically to allow logical flow while reading. You should also include essential methodology, but leave the details for your Methods section. Here, you can use headings to guide your writing and guide the reader through the story.

Figures

Figures are where you display your data visually. Clarity in figures and tables is more important than beauty. Similar to the results, display your figures in a logical order. Keep figures focused and use diagrams for complex ideas or methods.

Editorial Process

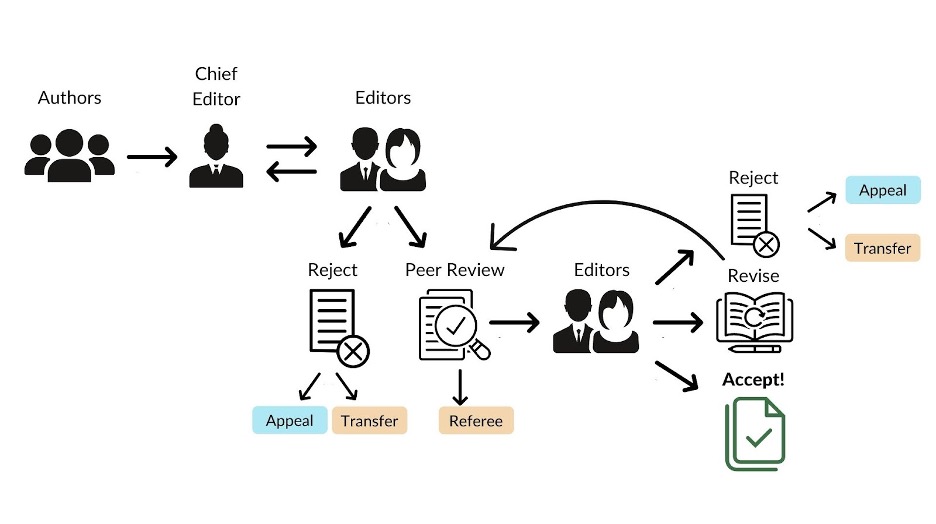

The editorial process starts with an author submission. In most cases, the editors are looking for significance and impact of your findings to the field and the quality of your data (how strongly it supports your conclusions). A strong candidate for review must address an interesting question for the field or solve a problem, represent advancement in the field, present strong data, and rule out alternative explanations to arrive at definitive conclusions.

Some reasons a paper may be rejected include: lack of data that supports the conclusion, significant technical flaws, ambiguous interpretation, insignificant results, lacking critical elements (such as mechanistic insight). Authors can appeal a rejection when they have additional data that addresses all concerns, factual errors in the reviews, and/or evidence of reviewer bias that the author can substantiate. Another option is to transfer the paper to another journal which often expedites publication.

Summary

- Select your journal carefully. Write for that journal.

- Focus on getting your main message across during your initial submission. Write a meaningful cover letter.

- Editors look for papers with potential so they will help develop a paper.

- Peer review should be a constructive process, revise carefully and with purpose.

- Editors are ultimately responsible for all decisions.

- Always feel free to discuss concerns with your handling editor.

Answers to questions below have been rephrased and shortened for clarity.

What skills are needed to be a good editor?

Flexibility in what you’re comfortable with and where your expertise lies. While you may not have hands-on experience with the papers you are assessing, you should possess an ability and willingness to learn. Also, trust in your skills. We’re all trained scientists and have the ability to read critically. Finally, you should want to read and enjoy reading papers to an extent because that will be the bulk of your work.

Could you share how "a day in your life" is as an editor of Comms Chem?

A lot of reading in general, but a typical day is difficult to describe. Dr. Ortner attends conferences, gives talks, attends meetings, talks to authors and reviewers, curates content and collections, and much more. The bulk of her work is to guide papers through the peer review process. This involves reading submissions, making decisions on their status, and assessing reviewer comments. If she finds a paper interesting, she will write her own review highlight to promote the research findings. Additionally, she writes press release pitches to the press team who may want to boost the paper.

Hannah Chu is currently an Entomology PhD student at UC Riverside. Her research focuses on blow flies in Southern California and their thermal adaptations in the face of climate change. You can find her on Twitter or her website. For more content from the UC Riverside science communication group “SciComm@UCR”, follow us on Twitter @SciCommUCR.

Comments