What Happens to Science When the Government Shuts Down?

The most recent government shutdown lasted an unprecedented 35 days from December 22, 2018, to January 25, 2019. While this shutdown affected many aspects of the day-to-day lives of those employed in the furloughed agencies, we wanted to know how it impacted those in scientific research.

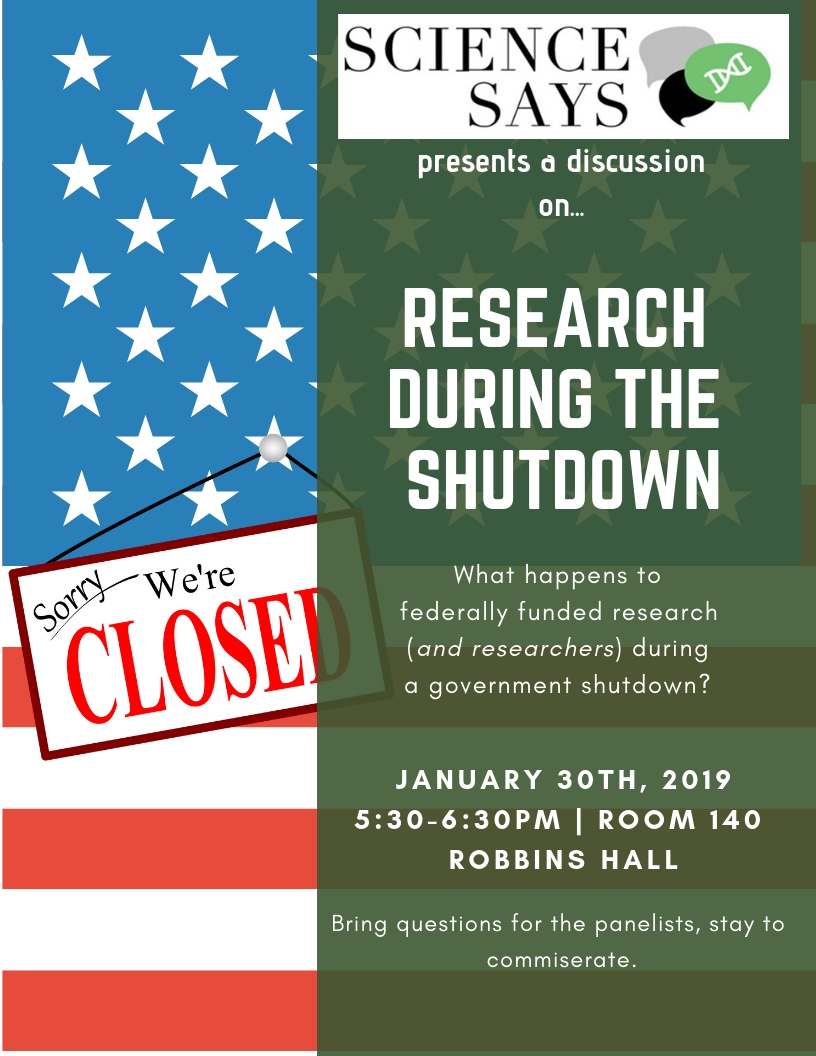

Andrew Groover, Cindy Kiel, and Ahmad Hakim-Elahi discussed the ramifications of the shutdown on science research at our January meeting.

Groover is a Research Geneticist with the US Forest Service and an adjunct professor with the Department of Plant Biology at University of California, Davis. He studies the developmental biology and evolution of forest trees and offered a firsthand view of what happens to a large-scale, long-term project, and all those employed to work on it, during a shutdown.

Kiel, the Executive Associate Vice Chancellor for Research Administration in the Office of Research, and her colleague Ahmad Hakim-Elahi, the Executive Director for Research Administration and the Director of Sponsored Programs, provided a detailed view of the institutional effects of such a shutdown and how it might affect science research as a whole, long term.

We appreciate Groover, Kiel, and Hakim-Elaji taking the time to talk with us and answer our questions.

Below is a transcript of our conversation, edited for clarity.

How does your position intersect with the government and how was your work affected by the shutdown?

Groover: The government pays me, so there is a strong intersection. I was sent home and not legally able to perform work. This can be incredibly challenging for research, especially for long-term projects like our work with trees as a model organism. We usually prepare for next year’s experiments by taking cuttings while the trees are still dormant, and the shutdown overlapped with that timeframe. Additionally, we have collaborators in Idaho who are relying on these samples, and if we cannot get them, this may delay a student’s graduation by a whole year.

"We’re told it is illegal to perform work unless we have an authorization to do so, but can be confusing as to what is covered...like reviewing papers for a journal on my own time?" - Groover

Kiel: I oversee all of the funding, and a bulk of the funding for research on campus comes from federal government on the order of ~$500 million. It was difficult for us to determine who was directly affected because stipend-based fellowships for students such as the NSF GRFP are not considered in that number. As a board member of the Council on Government Relations, I needed to work with federal agencies to understand their individual regulations for the shutdown and communicate that back to our constituents. Luckily, this was only a partial shutdown and our biggest sponsor, the NIH, was not closed. The hardest areas for us were projects involving the USDA or EPA.

1,142 NSF grant proposals were not reviewed, and 67 review panels were canceled. 13,000 NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program applications were received but the review process scheduled to start January 14 has been delayed. Widener, A. (2019, January 21). Policy Concentrates. C&EN, 97(3), 1-56.

Why make it illegal to work? Payment is an obvious problem but biological samples are important! Is it due to liability?

Groover: Yes. Even if the federal building was open and a non-federal employee was working and got hurt, no one would be there to respond. I could request specific employees for specific projects for specific amounts of time. So you can have someone work for a set amount of hours to maintain a project. And dedicated workers are frustrated they couldn’t work. The label of “non-essential” isn’t great.

Kiel: It is on the regulatory or oversight committees to determine who is essential or not, but we can’t always get a response. And those who were deemed essential had to work without pay.

Essential people are considered people who maintain safety, animal care, facilities.

Groover: Our fume hood broke during the shutdown, so the possibility of toxic fumes leading into the building is an example of unexpected consequences during a shutdown.

What did you actually do during the shutdown?

Groover: On the first day, I slept in! As it continued, I began to be concerned about how I’m going to pay people, then that I’m not going to be paid. What if we don’t get back pay? There was no communication about whether you would or not, only when it was included in the congressional resolution.

How do you communicate with the people in the lab? Can you?

Groover: There was a lot of confusion and uncertainty over whether the shutdown was actually going to happen, so communicating that the shutdown did indeed happen and what we can and can’t do was difficult. The fact that the shutdown started around the holidays when people are gone was also bad timing. We used emergency phone trees to communicate the information. I wasn’t allowed to use my work computer or email, despite getting notifications about the shutdown on those platforms. My lab employees are not funded by USDA directly, so they could still work, but a lot of business processes were down.

How does the length and timing of this shutdown affect research? How do you handle the uncertainty of the length?

Kiel: Our approach was to just go with it and hope for the best since we didn’t know how long it would last. Previous shutdowns were shorter and much easier to get past. As the agencies that were furloughed saw that the shutdown was going longer, they changed their approach and we adapted from there. The NIH was not closed, so those projects were fine. NSF funding was also unaffected, at least immediately, in that they provide the full amount of funds upfront to be administered and then researchers send in annual reports. USDA funding is under cooperative agreements, so there’s a lot more contact and communication that really ground to a halt. Based on the project, we have to tailor how we handle the situation. And this also affects other universities we work with; our collaborations are often set up through subsidiary awards, so when do you tell them they need to stop work because we don’t have the funds?

Hakim-Elaji: A difference between this and the shutdown during the Obama administration is that this shutdown was only partial, and the prior one was a total shutdown. During the total shutdown, stop work orders were sent very quickly; this time, NASA was the only agency to send out some form of stop work order. During the total shutdown, we were able to forward those stop work orders to the collaborating groups, but it was unclear this time because of no stop work orders.

What determines which agencies are closed?

Kiel: Agencies that did not already have an authorized budget from Congress were closed. A budget accounts for inflationary costs. Therefore, without an approved budget the agency works from last year’s budget, which means an automatic 2-3% cut. When in a continuing resolution [maintaining the previous year’s budget], the agency can use 90% of the funds until the new budget is approved, and it is up to the funding recipient to determine how it gets allotted.

How long, as a university, can we hold out in regards to funding our projects?

Kiel: For the most part we were able to keep research going. Grant applications were being accepted by grants.gov but the agencies were not picking them up, review panels were canceled…Given that the government is potentially only temporarily reopened, these processes may again be put off. This can result in big gaps in funding down the line due to time delays. But the University of California has a Principal Investigator (PI) Bridge Program available where PI’s can apply for funding to continue research until they receive funding from a grant. Because of the shutdown, we anticipate there will be an uptick in applications due to the delay in processing grants.

What happens if it closes again?

Kiel: There will be more uncertainty. What agencies are able or are going to renew funding?

Groover: There is less of a buffer in the system now. We had previous years’ funding that were fumes to run on during this shutdown, but that may not be an option.

"It was very interesting to hear about the effect of the shutdown from the perspectives of the university's research admins and [a] government scientist. Especially, on how the shutdown impacted the university's research, and what mechanisms are there (sic) to mitigate the negative impact of the shut down to the university's research community." - an attendee

Author: Sydney Wyatt is a PhD student at the University of California in Davis. For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on twitter @SciSays.

Comments