8 Bee Experts Weigh-In on Pollinator Decline & Cheerios’ Bid to Save Them

We've been hearing a lot about declining bee populations. As scientists, we're concerned about our pollinator friends. So we interviewed 8 entomologists, bee-keepers, and other pollinator experts to cut through the buzz about bees.

The Gist

Honeybees are okay, but wild pollinators are at risk. The biggest threat is habitat loss, but climate change, insecticides, and diseases also spell trouble. Certain agricultural practices can help, and we can all do our part by planting flowers instead of keeping grassy lawns and encouraging city planners to do the same. If you got one of those wildflower packages from Cheerios, consider ditching those seeds for native ones instead.

To bee or not to bee

We asked the experts whether or not bees are in trouble. The overwhelming response: WHICH bees? Honey bees are commercially managed by beekeepers and trucked around to pollinate crops from almonds to zucchinis. The "beepocalypse" first gained attention in 2006 when honey bees in the US were dropping like flies, especially during winter months. The varroa destructor, a nasty mite, is likely the main perpetrator along with diseases it spreads. Insecticides and fungicides could also factor in, but it's unclear how big of a role they actually play in the field. But honey bees are not even native to the US, and they're managed like livestock. So bees died, beekeepers upped their numbers, and now honey bee populations are stable, maybe even increasing.

But honey bees aren't the only bees – far from it – and they aren't the only insects that pollinate food crops and other plants, which whole ecosystems depend on. What's worse, when beekeepers cart honeybees across the nation, they carry parasites and pathogens that can spread to wild populations. Some wild bees ARE at risk, particularly solitary bees, some species of bumble bees, and other non-bee pollinators. The rusty-patch bumble bee is considered an endangered species in the US, and many other species are on the red list in Europe. While there are over 20,000 species of bees in the world and 4,000 in the US alone, we only have population data on a few. More research (and more funding) could identify at-risk pollinators.

People vs Pollinators

Pollinators face many perils, but most experts agree food and habitat loss dominate. For pollinators, food means flowers/plants and habitats mean undisturbed places for nests/hives/colonies/larvae. We actually compete with bees for homes and food. If a prairie is plowed to plant acres upon acres of soybeans, pollinators in that field lose their livelihood. If a forest is cleared for a housing development or a golf course, the flowers wild bees depend on go too. If you weed and mow your own yard, you too are contributing to pollinator decline. While we could probably live without golf courses and lawns, we do need homes and food. Planning developments, gardens, and farms with pollinators in mind can make a big difference. That means leaving ditches, parks, lots, and lawns in their natural weedy state whenever possible. If the weeds really must be cleared, plant flowers in their place instead of grass – preferably local flowers that vary in shape and color and flower at different times.

Apiaries in Agriculture

Farmers have an extra challenge. They need to ensure their crops have ample room to grow and don't get choked out by competing plants, but plowing or spraying stubborn weeds destroys habitats. Pollinator habitats can be managed within and around farms by planting cover crops, practicing crop rotations, or managing less-fertile land as refuges for insects. Technologies that help increase yield per acre may also help prevent more prairies, forests, or wetlands from being converted into farms. Insecticides that stop hungry bugs from mowing down crops can also mean bad news for pollinators. It's tough to study the specific role of insecticides, because any given bee might be exposed to multiple compounds at varying levels. These factors interact with other threats like poor nutrition and disease, so it's nearly impossible to identify a single, direct cause. The bottom line: anything designed to kill insects – from commercial insecticides to organic alternatives to home remedies – certainly can't help.

On the other hand, banning specific pesticides may not be the best approach. Farmers have to control pests somehow, and alternatives might not prove any friendlier to pollinators or farmworkers. Scientists are working to develop pest control methods that are more specific, and plants that produce their own defenses, so sprays aren't necessary. In the meantime, integrative pest management approaches that "balance the good guys against the bad guys" can help protect beneficial insects like bees.

The end all bee all

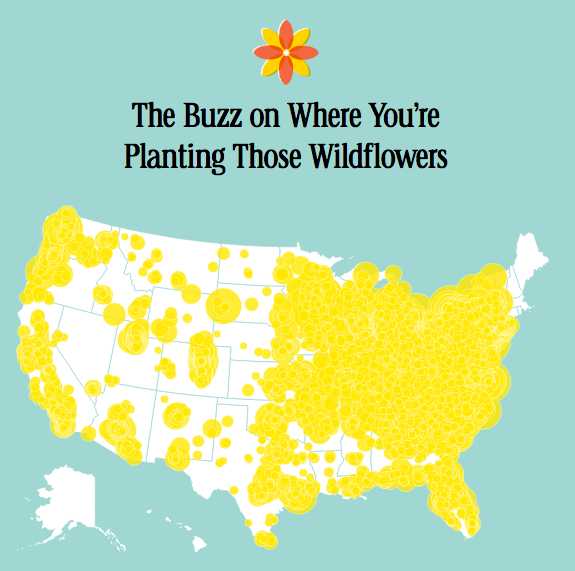

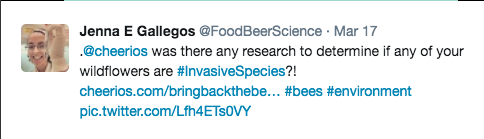

In short, there are many threats to pollinators, and we don't really have a good understanding of exactly which bugs are threatened. Such a multifaceted problem calls for a multifaceted solution, and no silver bullet is going to do the trick. But we know that habitat loss is a big concern, and we can all help by remembering pollinators when we make land-management choices. That's why Cheerios distributed 1.5 billion wildflower seeds for free. The idea is awesome, but experts worry the execution is not. Trouble is, no pack of wildflower seeds can possibly be native to every region in the United States. While Cheerios did their homework to ensure that none of the seeds spawn from known invasive species, scientists are still concerned. Some of the flowers included are considered noxious weeds and could prove problematic for farmers. These foreign flowers may also compete for pollination with native species, giving the invaders an edge, and potentially harming pollinators with a specific taste for native plants.

All our experts agreed that planting wildflowers is a great idea, but you should really try to plant flowers native to your home region. The Xerces society can be very helpful in that department, as can the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center and the Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder. That said, General Mills has really done some great things to help pollinators. As have other corporations including Bayer, Haagen-Dazs, Monsanto, and more. Their efforts should be applauded.

Want to know more?

Expert Q & A. Reader-friendly & expert-recommended sources. Scientific literature backing these claims.

A BIG THANK YOU to these great eight bee buffs:

Dalton Ludwick is a doctoral candidate in Plant, Insect and Microbial Sciences at the University of Missouri. His research focuses on the management of western corn rootworm, a serious pest of corn, with Bt proteins.

Rea Manderino is a PhD student at SUNY – College of Environmental Science and Forestry in Syracuse, NY. Her research has focused on the impact of gypsy moth presence in North America, and this has included examining the far-reaching influences of non-native organisms in our native ecosystems. Rea is also co-moderator of "Relax, I'm an Entomologist" on Facebook.

Val Giddings is a geneticist, an outdoor enthusiast, an amateur beekeeper, and a policy nerd. Like some folks have a wine cellar with varieties from around the world, Val has a honey cellar.

Dr Manu Saunders is an ecologist based at the University of New England, Australia. Her research focuses on beneficial insects that provide ecosystem services in crop systems, particularly pollinators and natural enemies of pest insects. She writes about pollinators, ecology and agriculture at https://ecologyisnotadirtyword.com/.

Jerry Hayes is the Honey Bee Health lead for Monsanto's newly formed BioDirect business unit. Before joining Monsanto he was the Chief of the Apiary Section for the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. In that role he was responsible for the regulatory health of the 350,000 colonies in the State of Florida, a state highly dependent on honey bee pollination for agricultural success. For the past 30 years Jerry has written a monthly column in the American Bee Journal called The Classroom and a book by the same name. Jerry is a founding member of the Colony Collapse Working Group, a science advisory board member for Project Apis mellifera (PAm), the Bee Informed Partnership, and he serves on the Steering Committee of the Honey Bee Health Coalition. He has been author and co-author on multiple research papers that delve into how to understand and preserve honey bee health. In Jerry's 35 plus years in the Apiculture Industry his overarching desire has been to create sustainable honey bee management practices while partnering with other segments of agriculture. The cornerstone of his career has been to educate others that honey bees are the key pollinators and the critical role they play in agriculture; while in parallel encouraging the development of multi dimensional landscapes for the benefit of honey bees and all pollinators.

Rachael E. Bonoan is a Ph.D. Candidate who studies honey bee nutritional ecology in the Starks Lab at Tufts University. She is interested in how seasonal changes in the distribution and abundance of flowers (i.e. honey bee food!) affect honey bee health and behavior. Rachael is also the President of the Boston Area Beekeepers Association and enjoys communicating her research and the importance of pollinator health to scientists, beekeepers, garden clubs, and the general public. More info on bees via Rachael's website www.rachaelebonoan.com or her Twitter @RachaelEBee.

Kelsey Graham is a pollinator conservation specialist. Her graduate work has focused on invasive species and their impact on native pollinators and plants. She has used an interdisciplinary approach to provide a comprehensive assessment of an invasive species, the European wool-carder bee (Anthidium manicatum), within their invaded ecosystem. She will be defending her PhD in April 2017, and beginning a post-doctoral research position at Michigan State University in Dr. Rufus Isaacs lab, where she will study how landscape features impact the local bee community.

Dr. Maj Rundlof is an ecologist and environmental scientist at Lund University in Sweden, currently visiting UC Davis as an international career grant fellow to work with bumble bees in Neal Williams lab. Her most recent research focuses on impacts of land use change and pesticides, particularly the disputed neonicotinoids, on bees and the pollination services they provide to crops and wild plants. A large part of her research is in the interface between conservation biology and agricultural production, aiming at exploring how we can support biodiversity while also facilitating food production. She has, for example, studied how farming practices influence plants, butterflies, bumble bees and birds as well as how created habitats influence crop yields and ecosystem services like pollination and biological control by pests' natural enemies. The bumble bee, one of these pollinating insects, is her favorite study organism.

Jenna E Gallegos is a PhD student at the University of California in Davis. For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on twitter @SciSays.

Comments