Soil Health is the Foundation of a New Green Revolution

Quick Summary

- Better soil quality often correlates with better crop health, just like the nutritional quality of our food typically correlates with improved human health. Read more to learn about the health of our soil.

We often think of soil as “just dirt”—something to be cleaned or discarded, but the truth is soil plays a crucial role in our food system. Soil is made up of microorganisms and nutrients that are required for crops to grow. Despite its importance, however, soil health has historically been disregarded in favor of prioritizing agricultural productivity. Fortunately, a new trend focusing on maintaining soil health has the potential to usher in a New Green Revolution.

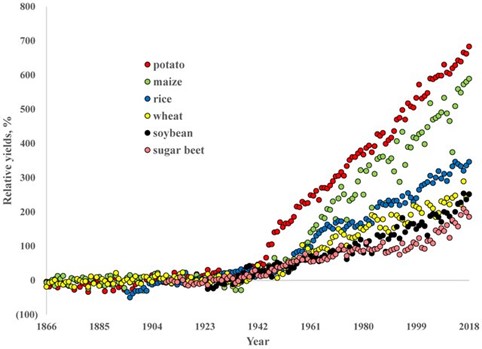

To understand soil's role in agriculture, we have to go back to the 1950s and 60s. Known as the Green Revolution, this period saw a notable increase in agricultural productivity through innovation in plant breeding and technological advances in agriculture. Mineral fertilizers and pesticides increased crop yields during the Green Revolution, thus providing plants with nutrients and reducing crop loss due to pests. These agricultural innovations were instrumental in improving food security during the population boom of the second half of the 20th century, but at an environmental price.

This environmental price resulted from the overuse of chemical pesticides and fertilizers, which has led to soil erosion and chemical runoff. Soil erosion causes carbon loss and essential plant nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, and chemical runoff disrupts biodiversity and causes water pollution. While the Green Revolution had many benefits, it was not without fault—one of its most significant faults was its impact on the health of our soil.

To feed the world sustainably, we must see soil as a living organism as opposed to an inanimate object—a vital piece of an interconnected biosphere rather than simply a means to an end. Both increased interest in reducing carbon emissions via the retention of carbon in the soil, known as soil carbon sequestration, and scientific advances that allow us to measure entire systems of chemicals and microbes in the soil have been instrumental to this shift from focusing on soil quality to focusing on soil health.

Like human health, soil health is difficult to define using one metric. Doctors use a wide variety of tests and metrics to assess different aspects of our health. Farmers and agricultural researchers assess soil health using a similar approach. Farmers must be aware of balancing crop productivity with soil health metrics like pH and soil organic carbon (SOC). Soil pH affects the nutrients available for plant growth, while SOC measures the amount of carbon that soil can capture from the environment, making it a popular metric for those interested in sustainable agriculture and a proxy for carbon sequestration. Furthermore, bioinformatics and other big data approaches have allowed scientists to simultaneously measure multiple soil health metrics, giving us a more comprehensive assessment of soil health than was previously possible.

To illustrate the harm that the Green Revolution caused, let’s focus on one widely used class of pesticides called fumigants. Fumigants are gaseous compounds commonly applied to the soil to control underground pests and diseases. Though there is no debate that fumigation succeeds in reducing pests, studies have shown that it also harms microbial communities and farmworkers. Beneficial microbial communities are important for nutrient cycling, breaking down crop residues, and stimulating plant growth. Therefore, fumigation destroys these communities and negatively impacts soil health and crop productivity. Moreover, fumigants’ ability to move freely in the atmosphere over great distances as gases puts farmworkers at risk of chemical exposure at doses that can cause chronic illnesses.

Of course, harmful microbial diseases and pests still need to be managed, so what other strategies can we use? Scientists are studying alternative methods to kill soil pests without harming the delicate belowground ecosystems. Chris Simmons, a Professor who serves as the Chair of the Department of Food Science and Technology at UC Davis, leads research on a potential alternative to soil fumigation called biosolarization. It uses a combination of microbes and soil heating to create soil conditions that are lethal to many pests but safe for humans. In collaboration with the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety, Chris and his research group have demonstrated the efficacy of biosolarization in almond orchards. Further monitoring of these fields has also shown long-term benefits to soil health.

Chris’ work is part of what some call the “New Green Revolution”—a response to the first Green Revolution, which will center on agricultural sustainability and productivity. The New Green Revolution will be an agricultural revolution that is truly green. Soil health is the foundation, literally and figuratively, of this New Green Revolution.

Emily Steliotes is a current PhD student in the Agricultural and Environmental Chemistry graduate group. Previously, she received a master’s degree in Biochemical and Molecular Nutrition from the Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University. Her dissertation work focuses on building a food informatics framework that connects the health and sustainability dimensions of food, from the chemical to the systems level.

Outside her research, Emily is passionate about career development and social innovation. Her most recent endeavor, The Job Feed, leverages her unique expertise to curate job postings in the food systems and sustainability fields.

For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on Twitter @SciSays.

Comments