Baloney Detection

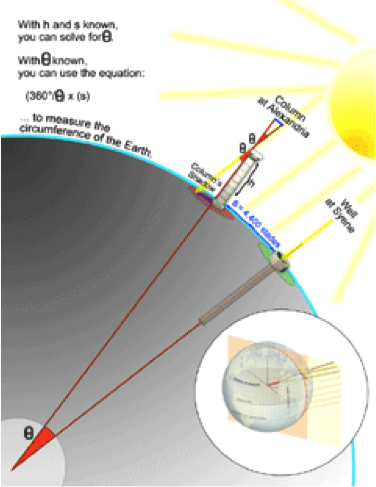

More than 2,500 years ago, the first evidence for a spherical Earth was discovered by the Ancient Greeks. Around 500 BC, Pythagoras noted that the moon was a sphere and reasoned the Earth was as well. A few hundred years later, Greek mathematician Eratosthenes used simple geometry to estimate the circumference of Earth. He had surveyors measure the heights of shadows cast by sticks in the ground. From this, he was able to estimate the Earth was 28,738 miles in circumference (the real number is 24,902 miles).

Today, we have images from spaces, satellites, and have even sent people into orbit and beyond. Yet, in the 21st century there are people who believe the Earth is flat (deemed flat-earthers), and there seems to be a growing number of them. The list of flat-earthers includes those with considerable influences, such as celebrities and YouTubers, as well as your average Joe. Flat-earthers connect with one another through social media and can even attend conferences together. When presented with evidence, of say photos from NASA, this information is deemed unreliable.

The idea of a flat-earth is itself pretty innocuous. No one is going to die or be taken advantage of for believing in a flat Earth. But what happens when the same line of thinking bleeds into other domains of life? In place of cancer medicine is faith healing, in place of counselors are psychics, and in place of vaccines are, well, not vaccines. Believing in these forms of pseudoscience can become a matter of life or death. Further, people are frequently swindled out of huge sums of money in exchange for pseudoscience. Ultimately, these issues can arise from an inability or unwillingness to think critically. If something seems too good to be true, it probably is. But, not all hope is lost. People can be taught and trained to think critically. Thinking critically is one of the core aspects of being scientifically literate. There are many different definitions of science literacy. A 1996 National Science Education Standards report used:

Scientific literacy is the knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts and processes required for personal decision making, participation in civic and cultural affairs, and economic productivity.

Science literacy is one-part domain knowledge (the content) and one-part understanding how science itself operates (the process). The process of science centers on skepticism, critical thinking, and experimentation. Of course, not everyone is going to become a scientist, nor should they.

How do we then train others to think like a scientist, to be scientifically literate?

To overcome this challenge, I created a new course at UC Davis for first and second-year undergraduates. The course is titled Living in a Post-Truth World: How to Build Your Personal Baloney Detection Kit." The first half of the title was intended to be provocative given the modern political era, but the second half is an homage to a book that is now more than two decades old. In 1995, astrophysicist Carl Sagan published The Demon Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. In the book, Sagan advocates for a more scientifically literate public, especially in the face of an increasingly technological society. Although the book was published two decades, many passages ring eerily true today:

"We've arranged a global civilization in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster. We might get away with it for a while, but sooner or later this combustible mixture of ignorance and power is going to blow up in our faces." – Carl Sagan

The book served as motivation and an outline for my course. The course met for 1 hour a week for 10 weeks, which in the grand scheme of things is not a lot of time. We opened the course by discussing Sagan's Baloney Detection kit chapter.

In the chapter, Sagan explores various tools to think skeptically about the world. These tools include quantifying whatever you can, entertaining multiple working hypotheses, and rejecting arguments based solely on authority. A lot of his arguments boil down to the line, "extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence." This chapter served as the backbone for the rest of the course.

We explored a different topic each week. The goal was to provide students with various tools to recognize and call out BS. For instance, we had an entire class on thinking like a scientist. Students had to form hypotheses and run experiments to determine the contents of black boxes. Another class centered on common advertising tactics, conveniently the week after the Super Bowl.

We had another class on what are commonly termed Fermi calculations. I began the class with a question: what is the circumference of the Earth? Naturally, no one knew such an obscure number and I stopped them from reaching for their phones. Instead, I described how Fermi calculations can be used to make such an estimate. The idea is that a series of reasonable guesses for various numbers in a calculation can end up giving an answer within the right ballpark – a back of the envelope calculation. Let's see how this works for the circumference of Earth:

- What previous knowledge do I have that might help me on this problem?

- I know that the distance from LA to New York is something like 3,000 miles. The exact number doesn't really matter.

- I also know there are three times zones from LA to New York. Thus, there are 1,000-ish miles for each time zone.

- Given 24 time zones around Earth, this puts us at a circumference of 24,000 miles.

- The correct answer? 24,901 miles. We were close, and, in this case, damn close. We didn't estimate 2,000 or 200,000 miles. We had the right order of magnitude.

Why is this useful? It can help you better understand big numbers that you might hear in the media or online. Suppose your friend is complaining about the "huge" budget of NASA. It would, of course, be useful to know what the budget of NASA is compared to the total budget each year. With a back of the envelope calculation you can determine that the yearly NASA budget is about 0.5% of the annual budget of the US, which is half a penny on the dollar. With some facts established, you can now have a reasonable conversation about its budget.

In addition to in-class projects and activities, students were required to analyze a pair of news articles. They had to apply their newfound baloney detection tools to critically evaluate the arguments in the news articles. I was impressed by their attention to detail, especially in being skeptical of numbers presented in the articles. They dug up original sources for numbers and explained if they found the evidence presented convincing or not.

Ultimately, I think the class was a small dent in a much bigger picture. I would like to see this type of skepticism and critical thinking taught throughout the education curriculum. This is not going to happen in 300-person university science classes that are chalked full of material. How do we re-design courses, and entire degrees, to be sure students are well-informed citizens when they leave university? This course will be offered again sometime in 2019. All the course materials are available here. It is also worth noting that Carl T. Bergstrom and Jevin West created a similar course, called "Bullshit Detection" at the University of Washington. All of their course materials are available here.

Easton White is a PhD Candidate in the Population Biology Graduate Group. His research involves using mathematical and statistical models to understand both ecological and evolutionary dynamics. He also teaches for the Biology Undergraduate Scholars Program and the non-profit Software Carpentry. You can read more about his work here.

Comments