Food Systems: Nourishing Inequality

Quick Summary

- Have you ever really considered where your food comes from, or the impact agriculture has on socioeconomics or the environment? Raisa Rahim takes a critical look at these intersections.

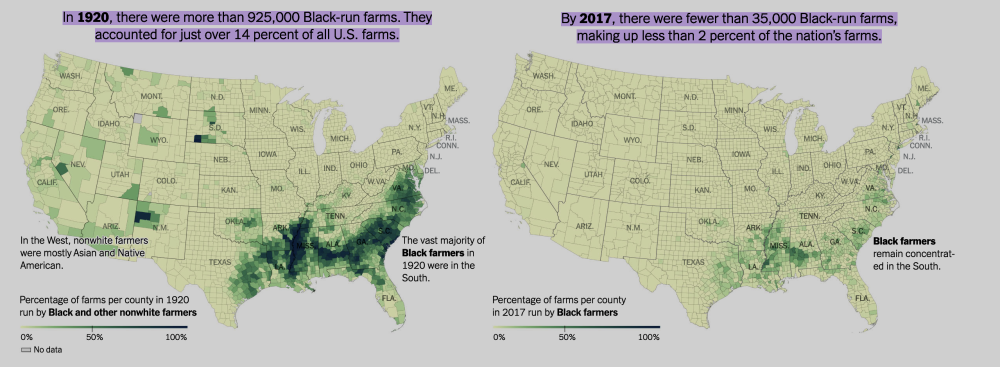

Now in her sixties, Willena Scott-White nostalgically reminisced about the family farm she grew up on, surrounded by other African American-owned farms. Such communities have a long and tortuous history. In the decades after the Civil War, Black sharecroppers cultivated their leased land (where they were often exploited as undervalued laborers). As they amassed generational wealth though, the retaliation began. Gaining momentum in the early- and mid-20th century, discriminatory practices ranging from harmful federal agriculture policy to outright violence drove Black farmers out of the business. They were forced to abandon about 16 million acres of stability- and autonomy-producing land. This has had lasting impacts — there are more than 96% fewer African American-owned farms today than a century ago (Figure 1), despite an increase of about 2% in the overall population in this same period. This loss is exacerbated by continued discriminatory financial backing, propagating historic inequalities incurred into the present day.

Food Systems Over Time: A Tale of Booms and Busts

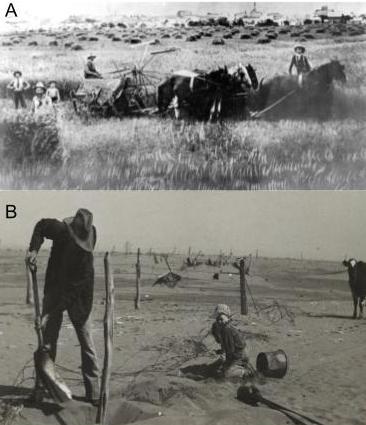

Food subsistence was originally achieved through a combination of nomadic hunting and gathering of encountered or tracked foods. The advent of agriculture made the production of food more reliable and permanent, in turn allowing for the development of long-standing, place-based societies where communities could put down solid roots. Early agriculture typically involved intense human- and animal-powered labor, with output being susceptible to the vagaries of an unpredictable ecosystem. This lack of control at the macro-level was countered by a principle of land stewardship.

As technology progressed (e.g. advanced farming tools), food systems became more dependable. Manipulating complex systems systems like the environment is likely to have unintended repercussions though, where indiscriminately imposing artificial constraints on the landscape throws the environment out of delicate equilibrium. One potent example played out in the American Midwest, where new technologies developed in the early 20th century dramatically increased field productivity. These practices had unforeseen consequences though, as the turnover of natural landscapes into unnaturally manicured farmland produced the conditions for the Dust Bowl that ravaged much of the Central and Southern Plains (Figure 2A, B). This sparked a mass migration of about 2.5 million people, where desperate migrants fleeing financial ruin faced hostility at their points of destination.

Though some changes (crop rotation, cover cropping, etc.) have been made to protect against another “natural disaster” like this, modern farming practices largely continue to value food yield over environmental feasibility. Crop monoculture, where large plots of land are used to grow only one kind of food at a time, is one vivid illustration of this extreme design. Though this strategy facilitates assembly line crop cultivation from planting to harvesting, this technique is problematic for several reasons. Backed by legislation that incentivizes overproduction, growing this homogeneous bloc makes it simultaneously easier for pests and diseases to spread and harder for pollinators to healthily manage the crop. Likewise, cultivating the field at maximum capacity leads to soil degradation, putting the land’s productivity at substantial risk of failure in the long-term. Farmers then turn to the use of relatively cheap synthetic fertilizers that negatively impact those who directly interact with them and those who incur indirect downstream effects. Consumers then pay the price for these unsustainable practices — applying so much pressure increases the likelihood that it will ultimately collapse.

The Price of Food Goes Beyond Grocery Store Signs

Until relatively recently, food production was managed by small- and medium-scale farms. With the inexorable pressure on all fronts (economic, legislative and global trade market dynamics), thousands of small- and medium-scale farmers have left the industry outright. With each passing year, holding onto the farm as it hemorrhages seems evermore futile. Some surrender a part of their identity, pivoting their job track to other industries. Because these rural communities are often based on this single industry, the ex-farmers likely need to shed their land and social ties to move to more populated and job-diverse regions to find work; this contributes to an ever-shrinking rural community. The rate of mental health emergencies has skyrocketed, an unfortunate throughline with other human-environment failures we have previously discussed.

While the majority of farms are relatively small, large-scale industrial farming is better able to withstand these macro-economic factors. Tied to the land by no more than purse strings, corporations are likely less motivated to act as land stewards compared to people who have generational ties to the land — they are incentivized to boost short-term productivity gains over long-term sustainability. As the profits for these products are reaped by distant corporate headquarters, money made locally does not stay local, further condemning rural communities to squalor.

In a Land of Plenty, Not All Have Access

With the rise of the suburb after WW2, supermarkets followed the buying power and open space now outside the city limits. As access to the American Dream was not racially equitable, residential red-lining transformed into supermarket red-lining. These disparities continue to the present day; it was found that the more people on public assistance in a given area, the smaller and fewer grocery stores were in it. In the past thirty years, grocery retailers have expanded to urban areas for their untapped potential for growth, but people still prefer to drive long distances to big chain stores for higher quality and quantity goods. This so-called “food desert” infrastructure has recently been critically examined, as the nutritional content of stocked products and social factors may be better predictors of food access.

Twenty-five percent of Native Americans are likely to experience food insecurity, despite thousands of years of sustainable, food-rich land stewardship. This was brought on by factors like restricted access to natural resources and to grocery stores, on top of the shift in diet resulting from forced relocation. On the reservation, there are high rates of metabolic diseases (e.g., this group has the highest prevalence of diabetes in the country), which are reduced when they return to their traditional cuisine.

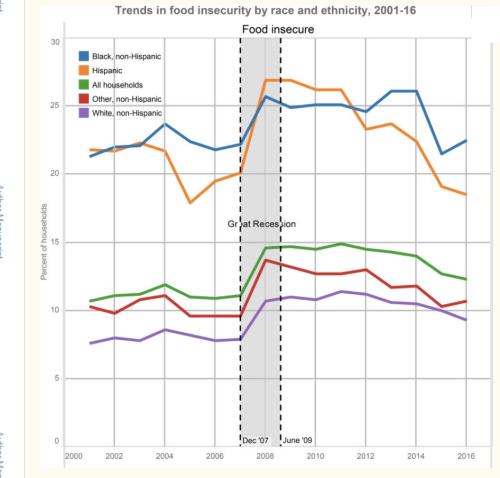

In 2020, 10.5% of all American households reported food insecurity; at least 34% of households of people of color were considered food insecure though. These disparities have largely held stable over time (Figure 3). Poor access to nutritious food is linked to poor health, increased healthcare costs at the individual- and government-level, and greater probability of incurring mental health challenges. While access to effective education is a fundamental barrier, poor nutrition hinders the ability to learn. These contributing factors drive persistent systemic inequalities.

Rotten From Top to Bottom

The inequities of the food system continue to the end of the cycle — the landfill. The anaerobic decomposition that results from heaping organic and inorganic materials builds up climate change-fueling greenhouse gasses. Though there are some protections, what byproducts are not aerosolized can leak into the water system, endangering the surrounding community. The human toll is significant — trash collectors and garbage dump workers are susceptible to a host of occupation-related illnesses, in addition to unfair job practices. Though composting is becoming more commonplace, food waste is still a massive problem. As this is simultaneous partnered with food insecurity, it is readily apparent that the inefficiencies of the food system need to be addressed.

So how can we move forward? Here are some suggestions:

- Government

- The economics of non-corporate food production does not add up. Restructure subsidies to not prioritize productivity and strengthen antitrust laws to protect small- and medium-scale farmers and the communities they are a crucial part of.

- Invest in creating an infrastructure to feed people where they live (urban greenhouses, etc) to cut down on shipping and emissions, reducing costs for the consumer and the environment. Develop community education programs for eating a healthy diet, increasing consumer demand that attracts healthy food retailers.

- Industry

- Corporate farming companies must stop their predatory behavior. Instead, partnering with smaller-scale farmers would foster a healthy community – this symbiotic relationship could make worker retention easier.

- Pay workers more – higher wages can be offset by reducing the use of added fertilizers through crop multiculture and rotation, animal grazing, etc.

- Individuals

- Check out this toolkit from the 2021 NorCal Symposium to learn how you can interact with food in a way that’s healthy for you and society at large.

- Eat local and in season. Though food pantries are becoming more common, there should be a more extensive and readily accessible way to donate. Fruit trees are not just ornamental. Reduce meat consumption, as farmed meats are much more resource-intensive than farmed plants.

Recommended media:

- “Braiding Sweetgrass” by Robin Wall Kimmerer

- “Kiss the Ground” documentary (2020)

Raisa Rahim is a fourth year PhD candidate in the Neuroscience graduate group. In the Integrated Attention lab at UC Davis, she is studying the accuracy with which humans remember complex objects such as abstract shapes and faces.

As a committee member on the Seminar Outreach for Minority Advocacy, she has played a role in brainstorming and implementing initiatives to support the equity of historically underrepresented scholars by giving them a platform to share their science and personal experiences.

For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on Twitter @SciSays.

Comments