An Honest Discussion on the Labeling of GMOs

GMO labels are misleading, frustrating science and science-advocates.

The marketing of non-GMO products agitates many scientists. Although the frustration towards fear-based marketing and the public's frequent misperception of GMOs is warranted, the blame on marketing companies is somewhat misplaced. Instead, disgruntled scientists must heed advice from marketers themselves: perception is reality. The large portion of the public sees GMOs as negative (Pew Research Center). To change this, we, as scientists and concerned citizens, must mend the public's attitude toward GMOs if we want progress.

"GMO" is a terribly vague term, but we are stuck with it (for now).

The term "genetically modified organism," or "GMO", is nondescript to scientists who actually study genetics (Escaping the Bench). There are multiple processes people can use to alter the genome of an organism (Biofortified).

Arguably, most modern plants that we consume have been genetically modified through evolution and selective breeding techniques used by farmers for centuries (Vox). Modern methods have evolved to hasten the process of improving plants, like mutagenesis or marker-assisted breeding. Recently, advances in scientific tools have allowed for more precision. Researchers can now change specific genes in an organism or add new genes to improve a crop, perhaps making it more resistant to drought or pests.

To many scientists, "genetic modification" describes all the approaches mentioned above, thus any product derived from any of those methods could be labeled as a GMO. However, many nonscientists may only describe the more modern techniques that enable precision adjustments to an organism's DNA as GMO. To have an effective, productive conversation, everyone needs to be talking about the same thing. The World Health Organization (WHO) does not clearly define GMO. GMO-scare sites have broad definitions. And the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) itself does not even use the term GMO, preferring instead "genetically engineered" to describe products cultivated using modern biotechnology.

I will use what the National Academies of Sciences defines as "genetic engineering" to define GMO:

Genetic engineering means the introduction of or change to DNA, RNA, or proteins manipulated by humans to effect a change in an organism's genome or epigenome. Genome refers to the specific sequence of the DNA of an organism; genomes contain the genes of an organism. The committee's definition of genetic engineering includes Agrobacterium-mediated and gene gun-mediated gene transfer to plants as well as more recently developed technologies such as CRISPR, TALENs, and ZFNs.

In layman's terms, a GMO has had its genes altered by humans using modern techniques that would not happen in nature*. GMO, in this article, does not refer to selective breeding or techniques involving mutagenesis, although it can be argued that those products have been "genetically modified".

The layman's definition is too vague for a scientist working with GE crops – they must speak in specific terms (jargon) within their community to communicate effectively. The field of genetic engineering has reached an advanced stage where one must specialize to understand all of its nuances. In reality, an average consumer will only ever care about the gist, and the underlined sentence is the gist.

*Nature is absolutely wild and always reveals unexpected phenomena. For all we know, nature may be employing weird genetic techniques we haven't yet realized. This is a major reason many scientists cringe at the term âunnatural.â However, many people may be more comfortable with the term "natural."

Products are being labeled as non-GMO as if there is an alternative.

Upcoming conversations about GMO labeling are unavoidable. The FDA has no requirements for GMO/GE labeling (yet) but is trying to establish a clear system. In the meantime, Vermont established requirements for GMO labeling and similar initiatives to label GMOs have been pushed in many states. In response, many companies have begun to label their products as non-GMO, leading to a confusing consumer landscape and a frustrated scientific community.

The annoyance (and sometimes anger) felt by scientists and science advocates or allies towards GMO labeling is warranted. Products that are not even available as GMOs are being labeled as non-GMO.

First, some products will never be genetically modified:

- Water

- Salt

These products are non-living and not derived from living organisms. Thus, there are no genes to modify along the production line. Consequently, scientists get rightfully upset about the products' nonsensical labeling because the labeling can play on a customer's lack of scientific knowledge.

Other products are not currently sold as genetically modified:

- Bananas

- Grapes

- Kale

- Peanuts

- Carrots

- Strawberries

- Almonds

- Many, many more...

These products give the consumer the illusion that they have a decision to make. In fact, there are only a handful of genetically modified crops available in the US (Genetic Literacy Project):

- Alfalfa

- Apple

- Argentine Canola

- Bean

- Carnation

- Chicory

- Cotton

- Creeping Bentgrass

- Eggplant

- Eucalyptus

- Flax

- Maize

- Melon

- Papaya

- Petunia

- Plum

- Polish canola

- Poplar

- Potato

- Rice

- Rose

- Soybean

- Squash

- Sugar Beet

- Sugarcane

- Sweet pepper

- Tobacco

- Tomato

- Wheat

For more information on any of the GMOs listed above, click here. Corn and soy are common GMO crops that are found in many products and are also fed to livestock used in meat and dairy production. (The use of GMOs in livestock cultivation further complicates the question about what is labeled.)

Non-GMO labeling, especially when a genetically engineered version does not exist, is misleading. However, nothing will be accomplished if we assign blame or stew in anger.

Take a hint from the grocery marketing community.

Current labeling guidelines are dictated by consumer requests.

Labeling products as non-GMO perpetuates the public's confusion. Hence, many scientists believe marketing companies are to blame for this. I intended to write this article about how bad non-GMO labeling schemes are, but I've concluded that many misleading food labels are the outcome of poor public understanding, not the cause.

I spoke with a seasoned grocery marketer, Pete Tucci (pictured left), about his company's experience with GMO labeling, and product labeling in general. Tucci has 40 years of experience in a private label company, assisting in the sales planning of merchandise. He has aided in the development of new items, interfaced with suppliers, and brought products to shelves.

I wanted to know why marketers would engage in labeling campaigns that are so seemingly destructive to the scientific enterprise. I would like to fully disclose that Tucci is my dad. Our relationship is the reason why a marketer would talk to someone with such great skepticism towards the role marketers play in our society.

Obviously, Tucci's goal is to sell his clients' products. When packaging a grocery item, companies need the labeling to be honest, but they want their product to stand-out. What makes an item stick out? At one time it was being "low cholesterol." Then it was "low carb." It has been "low sugar," "high protein," "gluten-free," "organic," and more. Now, being "non-GMO" makes a product stand out.

Who decides what makes a product stand out?

"[We] are looking to call out the meaningful attribute of that item... We try to be very transparent. We try to be very ethical and honest with the customer. We identify items as non-GMO." - Pete Tucci, grocery marketer

Tucci explained, "[We] are looking to call out the meaningful attribute of that item...We try to be very transparent. We try to be very ethical and honest with the customer. We identify items as non-GMO."

Personally, I was annoyed that identifying an item as non-GMO was seen as an ethical decision. Scientists work tirelessly to perfect GE technology with the goal of feeding a hungry, growing population in the face of extreme climate instability. Many scientists are driven by a moral imperative to find solutions to global problems, and many of those solutions involve genetic modification of organisms.

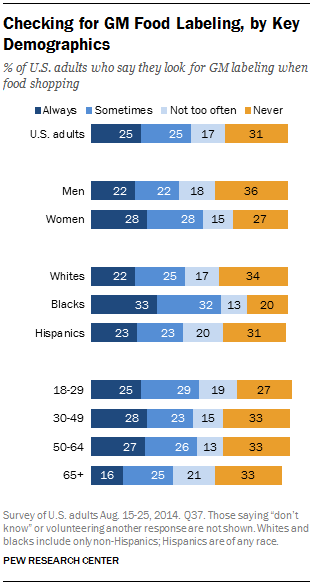

But then, Tucci elaborated, "Customers catch things on the shelf." If a customer wants to know what is in a product, we will tell them. Increasingly, the customers are asking if their products contain GMOs. Tucci's experience with customer concern about GMOs is not unique, PEW research center found that many Americans are concerned about GMOs, with 50% of U.S. adults always or sometimes looking for GM labeling when they shop for food (PEW).

Moreover, "If customers are demanding non-GMO, we are going to see the possibilities of doing that." Tucci's clients (and many companies in the grocery business) are going to respond to the demands of their customers. If public opinion continues to steer people away from GMOs, GMOs will not be sold as much.

Then Tucci spoke a harsh truth: "In marketing, perception is reality. We don't like to create a perception. We like to create the reality: This [the label] is what the item is. This is how you use the item. This is where we get the item." Grocery marketers do not want to surprise their customers.

"A scientist might know more than the average consumer when looking at product labels. If marketers are putting 'non-GMO' on an item that would naturally not be a GMO item, that does not mean they are trying to mislead the customer. They are just telling the customer that doesn't know [the product] is non-GMO. You might know it. But does every customer know it?" - Pete Tucci

Most people are not scientists. Most people don't know what GMO means. And sadly, a large amount of people fear GMOs.

As a last ditch, hopeful question, I asked, "Can a marketing company help to educate consumers about the science of GMOs?"

"Yes, I think. But, how much money can marketers put forward to tell the true story? Not enough. Not enough to overcome media, social media, free media. You're stuck giving in. Look at what happened to organics. That's the same thing that's going to happen to GMOs."

It is up to scientists to make perception equal reality. Marketers are not going to do it. They are neither equipped nor paid to educate the public.

Labeling can be good and consumers can be involved.

Transparency is generally good, in my opinion. I do want to know what is in the products I am purchasing. When buying food, consumers may consider the nutritional value of the product, its safety, its environmental impact, or the business practices of the company that produces it. To weigh the factors considered when purchasing grocery items, products must be labeled.

Personally, I do not hesitate to purchase a product that is a GMO. However, I am not the only consumer. Scientists are not the only consumers, and not all scientists study and think about GMOs. The reality is that many consumers are now factoring-in whether or not the products they buy are GMOs.

If scientists and industries aggressively push back on the labeling of GMOs, this will create a narrative that GMOs need hidden. Historically, when consumers demand clear labels on food, industry opposes and distrust towards the food industry grows (Union of Concerned Scientists, sugar, overhaul of nutrition labels). Science is part of the food industry and part of that distrust, whether we deserve it or not. The majority of GMO labeling is a consumer-driven initiative. Do scientists want to deny the wishes of the consumer?

No matter your answer to that, the push for transparency is not going away. Label Insight is a company aimed at increasing transparency in industry. They are working with the FDA to create "the industry's first scientifically accurate database of food ingredients, attributes and health claims." Label Insight released a report (not peer-reviewed) entitled "How Consumer Demand for Transparency is Shaping the Food Industry."They argue that "lack of product information creates distrust and confusion amongst consumers." Distrust and confusion are the exact opposite of what we want.

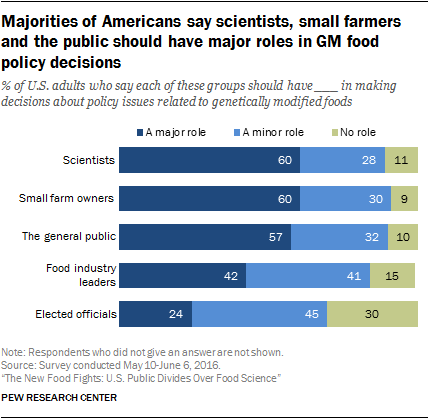

Furthermore, the majority of Americans do say the public should have a major role in GMO food policy decisions (PEW). If the public wants GMO food labeled, I think it should be. America is kind of democratic, right?

We need to change the public opinion, but how?

GMO education and advocacy efforts only go so far.

Instead of denying the wishes of the consumer to have transparent GMO labeling, we need to both educate the consumer and challenge the negative attitude around GMOs.

Educating the consumer is an enormous challenge. One study about the public perception of GMOs found that "[r]espondents who had relatively higher cognitive function or held illusionary correlations about GM food were more likely to have an opinion that differed from the scientific community." This means that opinions on GMOs is not based on education level alone, since intelligent people have been known to disagree with scientists. That is a hard truth to behold. We must figure out how to talk with those who do not understand the science and, at the same time, those who do and still disagree with us.

Importantly, increased understanding of science does not equate to an improved public perception of GMOs (Scheufele). Possibly because opinions are based on more than intelligence and understanding. They often result from gut reactions (disgust or anger), relying on intuitive reasoning that can be easily exploited by anti-GMO activists (Blancke, Scott). Thus, education about GMOs alone is not a promising tactic for improving consumer buy-in for them. But, it can help to make sure that both sides of the GMO labeling discussion are informed about the science.

A 2017 documentary, Food Evolution, offered both rational and emotional arguments in defense of GMOs. Food Evolution proudly displayed the wonders of GMOs and underlined how public misperception is preventing GMOs from helping farmers supply food. For example, the director chronicled the policy debate surrounding the use of ringspot virus resistant papaya in Hawaii. The use of the GMO papaya saved the papaya industry, but public backlash led to significant regulations on growing GMOs in certain parts of the state, the papaya being the only GMO crop allowed on the island. Although Food Evolution received praise for its accuracy, some still find it too fact-based to change faith-based opinions on GMOs. Nevertheless, Food Evolution is a solid effort at educating the public's more about GMOs.

The label is coming, let's use it.

Regardless of whether clear labeling of all GMOs in food is ever federally mandated, I believe most food companies will end up labeling their foods as GMO or non-GMO. If food labels can negatively change public perception, could they also be used to positively change public perception? Scientists from Dartmouth College propose GMO labels could be created to inform the public about the purposes of genetic engineering by subdividing GMOs based on their transgenic traits, like pest resistance or environmental stress response.

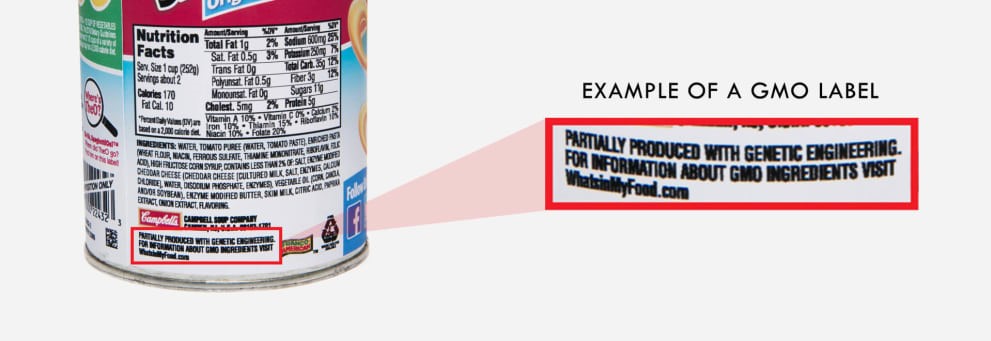

Campbell's has been vocal in mandatory national GMO labeling and acknowledges the evidence that GMOs are safe and are not nutritionally different than non-GMO counterparts. They operate with a "Consumer First" mindset to build trust with their customers. They are not ashamed of using GMOs in their products and offer information to curious customers on their website: What's in my food?. They also voluntarily label their products as containing GMO ingredients, but not with the Non-GMO Project's seal for "GMO avoidance." Instead, they use a simple label and direct consumers to their website. (Consumer Reports)

These efforts are great, but we need more of them. More importantly, we need to figure out how to change the negative emotions about GMOs that have been built by expert fear mongers. We need to do more than brood and preach to each other about how annoying it is. I don't know how to fix this whole mess, but do I think we need to learn how to actually market our product.

In the end, to really combat misunderstanding, the fear of GMOs must be replaced with the hope offered by them. GMOs can produce food in the face of climate change, feed a growing population, provide poorer agricultural communities with disease- and drought-tolerant plants. GMOs can have a major positive impact on our world if we let them.

Sam Tucci is a PhD student at the University of California in Davis. For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on twitter @SciSays.

Comments