How Our Early Life Upbringing Can Be the Root of Our Anxiety

Is your mother to blame for your constant anxiety? For decades, Sigmund Freud made it popular belief that all mental health problems were products of how your parents raised you. Although this idea fizzled out by the 1980’s, it still influences the way many clinicians treat their patients. However, your mother is not necessarily to blame for your anxiety, especially in a society where socioeconomic challenges can have a huge impact on parenting. Some mothers of low socioeconomic status, for instance, may need to divide their attention between working multiple jobs and caring for their children. Unfortunately, socioeconomic disparities that promote less attentive mothers may result in long-term repercussions for children. There is strong evidence suggesting that the level of your mother’s attention during your childhood can affect how you respond to stressors in adulthood. Even more alarming, these early experiences can modify your brain to affect how you parent your own children, consequently passing down anxiety-like behaviors for generations to come.

Is all hope lost for your future kids? Not necessarily, according to science.

How Do Variations in Maternal Care Affect Offspring?

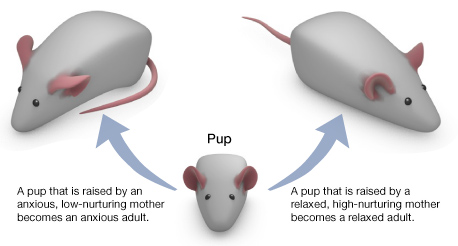

Low levels of care during early life have been shown to have a variety of consequences on children’s physiological and psychological health, including increased fearfulness and elevated cortisol levels in response to a stressor, such as a brief separation from parents. Cortisol is the primary stress hormone released as part of the body’s fight-or-flight stress response. Normally, cortisol is released in response to a stressor and received in the brain by a cortisol receptor; this ends the stress response cycle. However, too much cortisol can be detrimental to your physical and mental health. Dysfunctional cortisol release associated with low quality parental care may contribute to increased levels of depression, anxiety and self-esteem issues in young adults. Rat models have provided insights into the biology underlying anxiety-like behavior in offspring. Rat mothers naturally vary in how attentive they are in caring for their offspring. Offspring of mothers that are less attentive during their first week of life grow up to show higher anxiety levels and higher corticosterone (the rat equivalent to cortisol) release in adulthood. Interestingly, offspring born to low-caring mothers, but raised by high- caring mothers, are less anxious and release less corticosterone in adulthood. This suggests the environment is to blame for the difference in stress response later in life.

How Can an Experience in Early Life Have Long-Term Effects on the Stress Response?

Although these young rats receive differing amounts of care in just their first week of life, that is enough time to permanently alter their behavioral response to stress for the rest of their lives. How can that be? The environment, including experiences within that environment, can affect specific genes by marking them to be active (on) or inactive (off) in a process called epigenetics. In the case of rats raised by low-caring mothers, stable epigenetic “off” marks are put in place in brain cells that turn off the corticosterone receptor gene, resulting in less production of the receptor. Lower corticosterone receptor levels result in fewer opportunities for corticosterone to bind to the receptors, leaving increased levels of corticosterone in the body and prolonging the stress response. Unfortunately, this can lead to anxiety and other mental health consequences.

Can These Early Life Effects on the Brain and Behavior Be Reversed?

Offspring raised by low-caring mothers become low-caring mothers themselves in adulthood. In this vicious cycle, high anxiety levels and long-term health problems can be passed along to future generations through these epigenetic marks. How can this be prevented? Thankfully, these epigenetic marks are not as stable as scientists once thought. Rat studies demonstrate that early life interventions can be key in reversing the consequences of a less nurturing environment. For example, raising offspring born to a low-caring mother in a more nurturing environment actually reduces levels of the epigenetic “off” marks on the corticosterone receptor gene, leading to increased production of this receptor. This is unrealistic for humans at this time, but treating rats raised by a low-caring mother with a drug called Trichostatin A in adulthood also removes the “off” marks to increase receptor production and lower corticosterone release.

These findings have critical implications for humans and how the environment, such as socioeconomic stress, may negatively impact maternal care and children’s mental health. Instead of placing blame on the mother for giving less attention to her child, we should focus on understanding the outside factors that may contribute to her divided attention. Fortunately, these studies also inform society about interventions that can be further explored to bridge the gap that is caused by socioeconomic disparities among future generations of children.

Heather Mayer is a PhD graduate student in Biopsychology studying how the mother-infant bond is formed and maintained through epigenetic mechanisms. For more content from the UC Davis science communication group "Science Says", follow us on Twitter @SciSays.

Comments