How Prolonged Social Isolation During the Pandemic Can Affect Adolescents

It is an understatement to say that the pandemic has dramatically disrupted normalcy in one way or another. For months, going to work or school for many of us has meant not leaving the house. Additionally, we have all been advised to keep our distance from friends and family to avoid spreading the virus, making individuals--particularly adolescents--prone to feeling alone and isolated. Some teens may not even have access to electronic devices that allow them to virtually spend time with friends, making the lack of social contact especially hard for these individuals. Because socialization in early life lays the foundation for normal social behavior in adulthood, this begs the question: how harmful is extended social deprivation for an adolescent?

Adolescents are especially sensitive to their environment and their interactions with others because their brains are refining important connections and eliminating unnecessary ones. Additionally, critical neurotransmitter systems that regulate stress, emotion and social behaviors by communicating signals between brain cells are still maturing until early or late adolescence. Prolonged social isolation may alter the development of these systems, resulting in dysfunctional behavior. In fact, many studies suggest that social deprivation during this period can affect how adolescents respond to stress and can even impact cognition. Furthermore, some of these effects appear to be more prominent in females compared to males, suggesting that females may be more negatively affected by the inability to interact with their peers than males are. Luckily, evidence suggests that some of these harmful effects are not permanent and can be reversed when adolescents are provided with the right environment.

Social Isolation Can Alter Responses to Stress in Adolescents

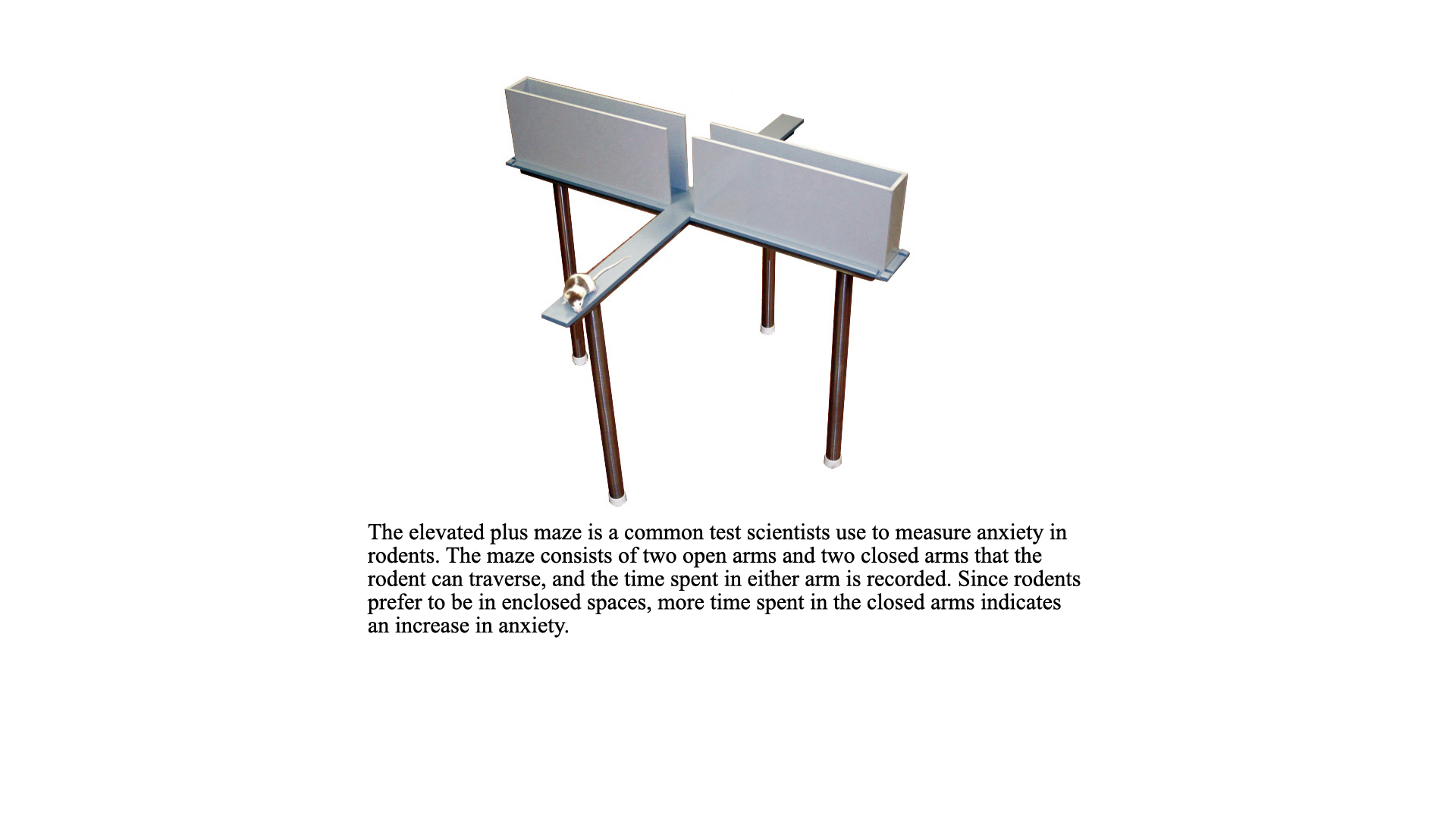

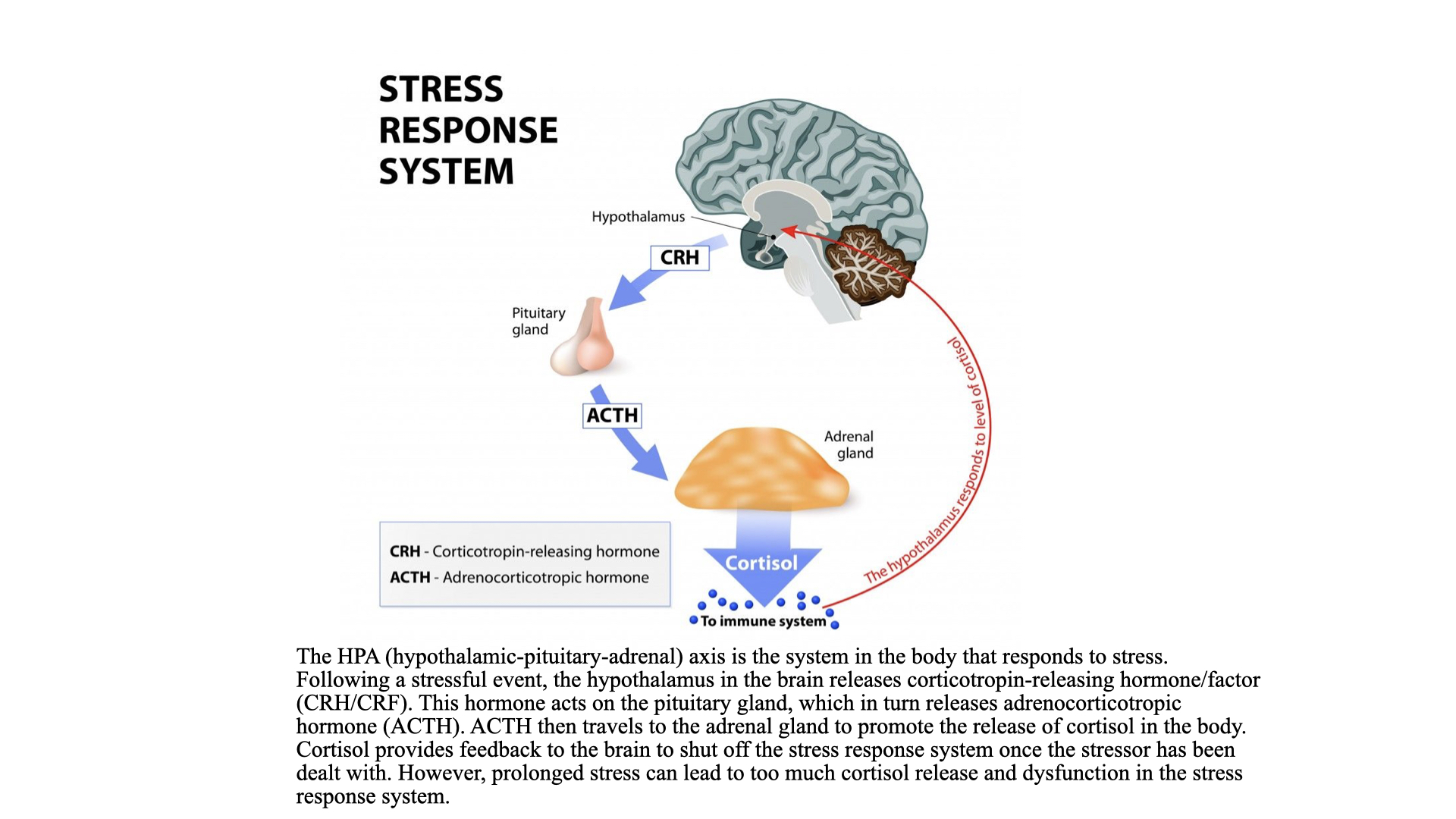

Given how vulnerable their brains are to disruption, it should be unsurprising that adolescents are sensitive to the effects of stress. A huge stressor in adolescence is peer relationships, although females report more friendship-related stress and remember more unpleasant events associated with their friendships than males do. This difference in how males and females respond to social stress is thought to be the result of a difference that develops early on in the activation of the HPA axis, the system in the body that regulates the release of a hormone called cortisol. Cortisol provides the fuel for the body to handle stressful situations. In support of this idea, teenage girls have higher levels of cortisol in their saliva following social rejection compared to adolescent boys. Evidence from animal studies indicates that an even bigger stressor, such as social isolation during adolescence, may also negatively impact the HPA axis. For example, rodents are highly social species that prefer to live in groups. Prairie voles and rats that are socially isolated during adolescence show an increase in anxious behavior, indicated by more time spent in the enclosed rather than the open area of an elevated plus maze. This anxious behavior is accompanied by an increase in components of the HPA axis, such as corticosterone, the rodent equivalent to cortisol, as well as corticotropin-releasing factor and its receptor, which when stimulated leads to the release of more corticosterone in the body. Blocking the ability for corticotropin-releasing factor to bind to its receptor reduces social isolation-induced anxiety. These findings suggest that social isolation during adolescence puts the HPA axis into overdrive, which may in turn increase sensitivity to stress.

Although both males and females show increased anxiety and an overactive HPA axis following social isolation, females seem to be affected to a greater extent compared to males. For example, one study showed that female rats that were socially isolated during adolescence spend a longer time recovering from stressors in adulthood than males do. They also show more anxiety-like behaviors on the elevated plus maze and release more corticosterone in response to stressors in adulthood. Because sex differences in HPA axis activation emerge early on in development due to hormonal influences like estrogen, females may be more sensitive than males to the effects of an early life stressor such as social isolation.

Social Isolation Can Affect Learning and Memory in Adolescents

In addition to causing increased anxiety, social isolation in adolescence may also lead to memory impairments. Social isolation in adolescent rodents causes deficits in spatial memory. Many factors may contribute to this impairment, including alterations in a variety of molecules that are involved in promoting the formation of connections between neurons. For instance, levels of molecules promoting memory formation are decreased following social isolation in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region critically involved in the regulation of learning and memory. Interestingly, isolated animals also have a thinner prefrontal cortex compared to controls, which may result in less cognitive capacity. Adolescent social isolation has also been found to reduce the ability to make new brain cells in another brain region important for learning and memory, the hippocampus. Since new brain cells can be important for forming new connections in the brain that are crucial for learning, this decrease may negatively impact the ability for isolated adolescents to learn and form memories.

Can These Changes in the Brain Be Reversed?

Although lack of social contact in adolescence can detrimentally affect the brain, luckily some of these deficits can be reversed. One study showed that providing previously isolated animals enrichment like toys improves performance on a spatial memory task, increases cortical thickness, and reduces anxiety in the elevated plus maze. Another found that resocialization can also reverse some of the maladaptive behaviors seen in isolated animals. Together, these studies indicate that prolonged social deprivation in adolescence can alter neural systems that are important for the normal regulation of stress responses and cognition. Further, adolescent girls may be more sensitive to some of the effects of social isolation than boys are because of sex differences in the way these systems respond to stress. Thankfully it seems that changes in the environment and resocialization with peers can lessen the long-term impact that social deprivation may have on adolescents during this isolating time.

Heather Mayer is a PhD graduate student in Biopsychology studying how the mother-infant bond is formed and maintained through epigenetic mechanisms.

Comments